Mucus, Dehydration and Asthma - everything you need to know!

Mucus in the respiratory tract plays an important role in respiratory health by trapping dust, pollen, pollutants and bacteria. Dr David Marlin discusses mucus (in detail!), what is healthy mucus, why it becomes unhealthy and what can be done to help.

Dr David Marlin

Scientific & Equine Consultant, 13/02/2020

Healthy mucus is difficult to see...

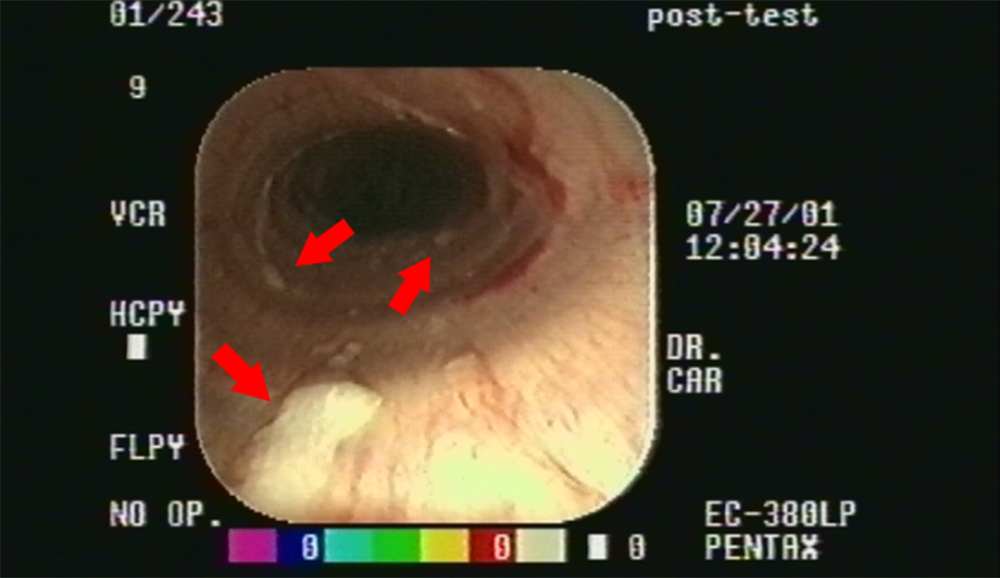

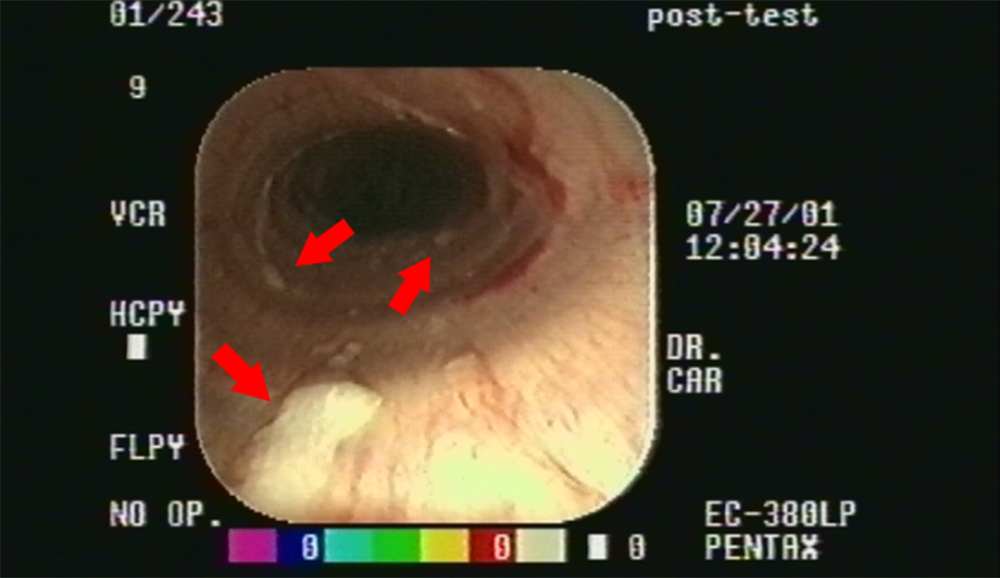

One of the key features of a healthy respiratory system is a thin layer of almost invisible mucus which lines the airways. Even when a horse is being ‘scoped, if the airways are healthy it can be very difficult to see any mucus. However if we do a tracheal wash (where saline is passed down the endoscope and into the windpipe and then aspirated (drawn out) or a deep lung wash (bronchoalveolar lavage - BAL) we can see the mucus in the sample retrieved from the lungs. In fact, if we aspirate a clear sample with no visible mucus that’s a sign that we haven’t managed to get a good sample. In contrast, when horses are sick we can often see large streams or clumps of thick, yellow, green or brown opaque mucus in the airways when we ‘scope horses or we may even see mucus at the nostrils. This is referred to as mucopurulent discharge and a sure sign that there is inflammation and or infection present. So what is mucus, what does it do and what changes it from healthy mucus to mucopurulent? Let’s start by look at healthy normal mucus.

Mucus is slimy, doesn’t mix well with water and is a secretion that is produced by specialised cells known as Goblet cells, often in groups (glands), for the primary function of lubrication and protection. Although it doesn’t mix well with water, ironically mucus is a water-based substance and is mainly formed from mucins, which are large proteins with sugar molecules stuck on them. Its this combination that makes mucus “sticky” and “slimy”. Mucus is produced in the nose, the lungs, the eyes, the gastro-intestinal tract and the reproductive tract. Mucus also serves to help prevent surfaces drying out and becoming sticky. This is especially important in the eyes and in the lungs. In the lungs the very small airways have a tendency to want to collapse inwards on themselves, especially during breathing out as the lung volume becomes smaller and the airways are compressed. Mucus and lung surfactant are vital to prevent the airways closing under high surface tension as once they collapse and shut, it is difficult to reopen them.

Normal healthy trachea – no visible mucus

In the airways, one of the key functions of mucus is to trap dust, pollen, pollutants & bacteria

The airways have specialised cells with hair-like protrusions called cilia which beat and continually move mucus from the smaller to the larger airways. The mucus travels up the trachea (windpipe) and most is swallowed, but when there is an excess this can be coughed up and or exits via the nose. So mucus is continually being produced and cleared from the lungs. There are several situations however when excess mucus is produced. In people the condition cystic fibrosis is a genetic defect that leads to the production of excessive, thick and sticky mucus in many parts of the body, but the lungs are especially badly affected.

Horses do not have as far as we are aware any comparable condition to cystic fibrosis. However, if horses have a bacterial or fungal infection in the lungs, then this leads to excess mucus secretion and the mucus changes from its normal semi-opaque white appearance to a thicker and yellow/green/brown appearance. This is referred to as mucopurulent; a combination of mucus and pus. Pus is a combination of dead white blood cells, bacteria, serum (from the blood) and tissue fragments. In the case of viral infection the amount of pus produced and hence mucopurulent discharge tends to be less.

One consequence however of respiratory viral infections such as influenza (flu) in horses is that it kills the ciliated epithelia. This means that clearance of mucus is slower and this provides a perfect environment for bacteria to multiply and cause infection. Hence why secondary bacterial infections are so common after flu. The ciliated epithelial cells also take around 4-6 weeks to regrow; hence why recovery of the lungs from flu can be slow.

Endoscopy of the trachea after exercise with clumps of mucus clearly visible (red arrows)

Dehydration plays a central role in equine respiratory health

The other circumstance in horses (and people) in which the mucus is affected is in any inflammatory condition. Inflammation leads to an increase in mucus production. In the airways the increased mucus leads to airway obstruction as the excess and often thicker mucus moves more slowly. This can lead to difficulty in breathing (dyspnoea) and reduced exercise performance. Horses with respiratory disease also cough, which is one of the mechanisms for helping to clear mucus from the airways.

Dehydration plays a central role in equine respiratory health, particularly in horses affected by equine asthma and during travelling. As we discovered before, mucus is water-based. It therefore follows that dehydration leads to thicker mucus which is harder to clear from the airways. This can lead to airway obstruction, decreased exercise tolerance, decreased performance and an increased risk of bacterial infection in the lungs. The risks of dehydration are particularly compounded by transport. During transport horses tend to become dehydrated due to decreased water intake and increased water loss (sweating, increased faecal water) but in addition, the head-up position also slows the clearance of mucus, allowing the growth of bacteria. So maintaining hydration for horses affected by equine asthma, or with respiratory infections or any horse during travelling is especially important. Whilst the advice for people in a similar situation from doctors is “drink plenty”, in horses the solution is not as simple.

Strands of mucus visible during a tracheal wash (sampling of the fluid lining the trachea by instillation and aspiration of saline)

What can be done to help healthy mucus?

Ensuring excess water is always available (i.e. 2-3 buckets instead of 1 bucket), feeding soaked or steamed forage and adding salt and or electrolytes to feeds are important. Avoiding small bowl or noisy automatic waterers is also a good step, as a number of studies have shown decreased water intake from these. If these are installed then using buckets for horses affected by equine asthma (or impaction colic) would be advisable. During transport, maintaining hydration is extremely important. Avoid travelling in the hotter part of the day and provide steamed or soaked forage or haylage continuously, especially on journeys over an hour. Make sure you take water and offer this to the horse as soon as you stop and avoid driving for more than 4h at a time without a stop.

How can Haygain help?

Haygain is committed to improving equine health through research and innovation in the respiratory and digestive health issues. Developed by riders, for riders, we understand the importance of clean forage in maintaining the overall well-being of the horse. Our hay steamers and ComfortStall are recommended by many of the world’s leading riders, trainers and equine veterinarians.