31/03/2021

Laminitis in Horses: What Every Horse Owner Needs to Know, Part 1

We explore what you need to know about the complicated condition of Laminitis.

Laminitis – the word strikes fear in the hearts of horse lovers as surely as this painful condition attacks the integrity, strength and function of the horse’s hooves. Maintaining the integrity of the horse’s hoof is essential to the soundness and health of the horse: “No hoof, no horse” is as true today as it was when that old saying originated.

If you suspect your horse is experiencing laminitis, stop reading this article and call your vet immediately: Laminitis is an equine emergency. Left unchecked, laminitis can become so debilitating that the only humane option is euthanasia.

Otherwise, read on for what every horse owner needs to know about laminitis. In Part One, discover: What is laminitis? What are the signs of laminitis? What causes laminitis? In Part Two: What precautions may prevent laminitis? What are the treatments for laminitis?

What Is Laminitis?

Laminitis is an extremely painful condition in the horse’s hoof that results from the disruption of blood flow to the laminae. The laminae secure the coffin bone, also known as the pedal bone, to the hoof wall.

Inflammation weakens the laminae which causes the coffin bone to separate from the hoof wall. The weakened connection allows the coffin bone to rotate, sink downward, and eventually penetrate the sole. At that point, the horse’s health, comfort and ability to function are so severely compromised that euthanasia can be the only humane option. Exactly how laminitis occurs has not yet been clearly identified. While we know that inflammation in the body can result in inflammation of the lamellae in the hoof, the exact mechanism remains unclear.

Consider this: Because the coffin bone is the very last bone at the bottom of the horse’s leg, if the coffin bone is not securely attached to the hoof wall, the hoof cannot support the weight of the horse. Without that support, even standing or walking can be excruciatingly painful. Imagine that you have inflammation underneath your toenails and have to support your weight on them as you go out for a jog – that’s essentially what a horse with even the mildest case of laminitis feels.

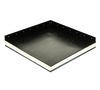

Photo: Vetfolio

The terms “laminitis” and “founder” are often used interchangeably, so what’s the difference? It can be confusing. “Laminitis” is often used to describe both the initial sudden onset of acute symptoms such as pain and inflamed laminae as well as the chronic, long-term condition in which the coffin bone rotates. However, “founder” is more often used to describe chronic, long-term laminitis.

When laminitis is diagnosed early and the underlying cause is corrected quickly, ongoing treatment and/or management may be enough to keep the horse functioning, healthy and pain-free for years. However, if laminitis is left undiagnosed and untreated, the consequences to the horse are grave.

What are the Signs of Laminitis?

So subtle that it is often overlooked, a horse’s reluctance to move forward normally is a reliable sign that something is wrong, and coupled with other signs, can provide enough clues to diagnose a case of laminitis.

Usually the front feet are most likely to be affected by laminitis, and lameness due laminitis is worse on harder ground. Another sign is the horse’s backward-leaning stance as it attempts to take weight off its front legs, where laminitis most often occurs, and seeing the horse lying down more frequently than usual to relieve the pain of weight-bearing on inflamed feet.

“Bounding pulses” in the horse’s feet, and hooves that are warmer to the touch than normal are signs that you can monitor. Ridges that ring the horse’s hooves are an indication that the horse has suffered from laminitis in the past, and past incidences of laminitis are usually a reliable predictor of future susceptibility. Sensitivity to pressure applied to the sole of the hoof with “hoof testers” such as most farriers use also point toward a diagnosis of laminitis.

An early-warning sign of the potential for laminitis is obesity. The low tech rule of thumb for determining if your horse’s weight is acceptable is to run your fingertips lightly but firmly across your horse’s barrel from front to back. If you can’t see the ribs but you can feel them, your horse’s weight is likely in an acceptable range. If you can’t see the ribs and you can’t feel them unless you apply very strong pressure, your horse is obese.

Obesity isn’t a nasty word – it’s a warning sign. Horses that are obese, and especially those horses prone to put on weight easily, are at greater risk of laminitis than the general horse population. Look for fat deposits or “pockets” on its hindquarters or a cresty neck especially if the fatty crest is hard. If you are in any doubt about your horse’s weight, consult with your veterinarian.

What Causes Laminitis?

Laminitis is actually a symptom of problems within the horse’s system, resulting most often from its feeding and exercise management, or hormonal or genetic conditions. Its causes are diverse, and what causes laminitis in one horse can be entirely different for another horse.

One of the most common nutritional causes is known as “grass founder”, which can occur when a horse that is unaccustomed to grazing is turned out to graze too long on lush pasture grass. Rich in sugar, especially at times of new growth, and with higher sugar content early in the morning and late at night, that gorgeous green grass has the potential to be a horse’s worst enemy. It’s safer and healthier to begin with short periods of grazing to gradually accustom the horse’s system to rich grass and then to gradually lengthen the time spent grazing.

Feeding excessive amounts of grain or concentrate feed can overload the horse’s digestive system with soluble carbohydrates: Sugar and starch. When they move into the hindgut, they begin a process that results in the release of toxins into the hindgut, and from there into the bloodstream.

Any change in feed should be made gradually, whether it’s a change in the type of feed such as moving from dried hay to pasture grass, or between one type of hay or brand of grain to another. Abrupt changes in feed can increase the risk of laminitis as well as the risk of colic, and severe colic can also cause laminitis.

Feeding excessive amounts of grain, treats and even hay, over time can cause laminitis as a result of the horse becoming obese. And obesity can occur as readily from lack of exercise as from overfeeding: for example, a horse that is laid up due to injury, or a horse that has recently retired.

A horse accustomed to a specific amount of exercise can rapidly gain weight if its feeding regime stays the same when its exercise is reduced or curtailed altogether.

Weight gain can also occur due to endocrine or metabolic issues such as Thyroid Dysfunction (TD), Equine Metabolic Syndrome, Equine Cushing’s Disease or Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID), and other conditions. Increasing numbers of horses are being diagnosed with these issues and one of the unfortunate results for these horses is the increased risk of laminitis or chronic founder.

Although being a particular breed or type of horse is not precisely a cause of laminitis, laminitis seems to strike some breeds and types with greater frequency. Owners of ponies, Arabians, native breeds, warmbloods and baroque breeds should pay particular attention to horse care and management of any predisposing elements in the laminitis puzzle.

“Road founder” or laminitis caused by riding too long and/or too persistently on a hard surface such as a road or an arena with fooling that is too hard for horses to safely work. This cause was more prevalent in the past, when horses were used more frequently as working animals for the transportation of people and goods.

“Supporting limb laminitis” famously came to widespread attention when Barbaro won the 2006 Kentucky Derby, then suffered multiple fractures two weeks later, and developed SSL. Despite having the best of care, his laminitis could not be controlled or reversed and Barbaro was euthanized.

High fevers can also cause laminitis, from toxins released by bacteria during womb infections such as a retained placenta, to the aftereffects of a severe colic. Fever and inflammation in any part of the horse’s body can trigger laminitis.

Stress takes a toll on horses, as it does on humans, including dramatic and/or abrupt changes in environment and/or frequent travelling.

TRENDING ARTICLES

-

BEFORE YOU GO

Get the Haygain Newsletter

Subscribe for the latest news, health advice, special offers and competitions. Fill out the form at the bottom of this page.